Picture this. You’re walking through the Eugene Saturday Market on a beautiful spring day. A cool breeze rustles the freshly-bloomed leaves on the maple trees. You can hear the drum circle echoing through the park blocks, and smell the aroma of weed and authentic, local food that lingers in the air. You look around at the art for sale eyeing the kaleidoscopes, bongs and psychedelic paintings. Eugene residents in tye-dye shirts are dancing their hearts out. You wonder to yourself: When did Eugene become the epitome of the hippie movement?

You can thank the renowned author and leader of the ‘60s counterculture movement, Ken Kesey. As a Eugene local and an alum of the University of Oregon, Kesey found numerous ways to leave a legacy in his hometown.

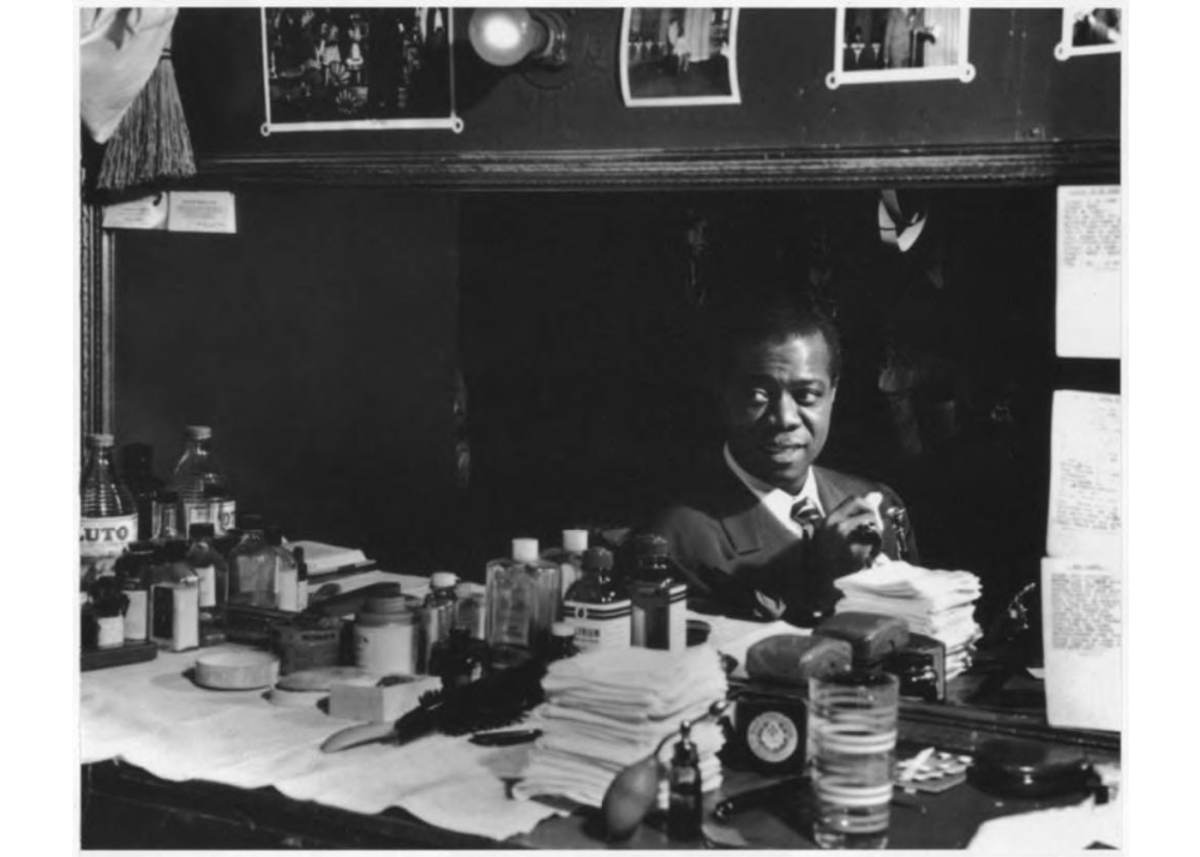

Kesey was born in 1935 in La Junta, Colorado. Shortly after, his family relocated to the Eugene area. However, Kesey’s initial attraction to the counterculture movement didn’t occur in Eugene but began after he was offered a prestigious scholarship for a writing program at Stanford University. A major shift in Kesey’s personality and writing style occurred when he became a paid subject of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) experiments, according to history writer Robert McNamara from ThoughtCo. This led Kesey to become fascinated with the potential for cognitive changes in the mind after ingesting hallucinogenic drugs.

Kesey’s creativity flourished in combination with psychoactive chemicals. Soon after, his career took off as a result of his newfound inspiration from LSD, according to McNamara. After writing “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” in 1962, Kesey’s rebellious, non-conforming attitude encompassed his reputation. It was no surprise when Kesey set off on a cross-country road trip with a group of his eccentric friends. The group named themselves the Merry Pranksters; they drove thousands of miles in an exuberantly painted school bus that they named “Furthur.” The Pranksters traveled with copious amounts of the then-legal drug LSD and claimed to be filmmakers anytime they were pulled over by police on their trip — pun intended.

The Pranksters eventually made the journey back to the West Coast in 1965 in order to hold a series of bizarre parties they coined “The Acid Tests.” At this point, the Pranksters established themselves as a well-known group of individuals who decided to abandon the status quo. People from all different walks of life attended their parties including poet Allen Ginsberg and journalist Hunter S. Thompson. The Merry Pranksters’ experiments with multi-media art projects, psychedelics and free-form rock music (ever heard of the Grateful Dead?) were further solidified in Tom Wolfe’s 1968 novel, “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.” Kesey and the Pranksters became signifiers for individuality and freedom within the counterculture movement as they set the standard for non-conformity within the hippie community for generations to come, according to The Furthur Down the Road Foundation.

Towards the end of the 1960s, Kesey returned to Oregon after being arrested for the possession of cannabis. Once released, Kesey continued to write, raise his family and teach at the UO. He died in Eugene on Nov. 10, 2001. Kesey remains an important symbol of Eugene’s uniqueness after spending the peak years of the counterculture movement building a legacy based on individuality and the freedom to express. It is likely that many members of Kesey’s loyal community followed in his footsteps and relocated to the funky town of Eugene, Oregon.

In addition to the nonconformist and free-spirited attitude, Eugene offers various tributes to Kesey. His undeniable influence resulted in his statue being erected on the corner of Willamette Street and Broadway, known as Kesey Square. Coined “The Storyteller,” the statue depicts Kesey reading to his three grandchildren. Plus, the aforementioned “Furthur” now resides on the Kesey family farm, just outside of the Eugene city limits.

Kesey’s granddaughter, Kate Smith, introduced the Kesey Farm Project in 2016. This initiative “works to host programming that support[s] emerging writers and artists from all backgrounds, encouraging collaboration and exploration… for the next generation of creative thinkers,” according to Kesey Farm Project website. Although the farm is closed to the public, anyone interested in visiting the farm can join the Kesey Farm Project’s mailing list in order to stay updated on visitation opportunities. Editors note: during the creation of this article, Green Eugene reached out to Kesey Farm Project and has yet to hear back. Any comments will be updated in the online version of this story.

The University has done its part in memorializing Kesey as well. According to The Ken Kesey Collection at the University of Oregon Libraries, his archives of manuscripts, artwork, collages and photographs dating from 1960-2001 have been purchased and will be preserved at the Knight Library for the foreseeable future. The special collections room is worth checking out next time you find yourself on campus; it is a great privilege to have access to the raw materials produced by one of the counterculture’s founding fathers.

As Eugene continues to develop into the quirky city that we all know and love, Eugenian’s are encouraged to remember who inspired the city’s original spunk. Next time you find yourself appreciating the weirdness of Eugene, you’ll know to thank Mr. Ken Kesey and his band of Merry Pranksters.