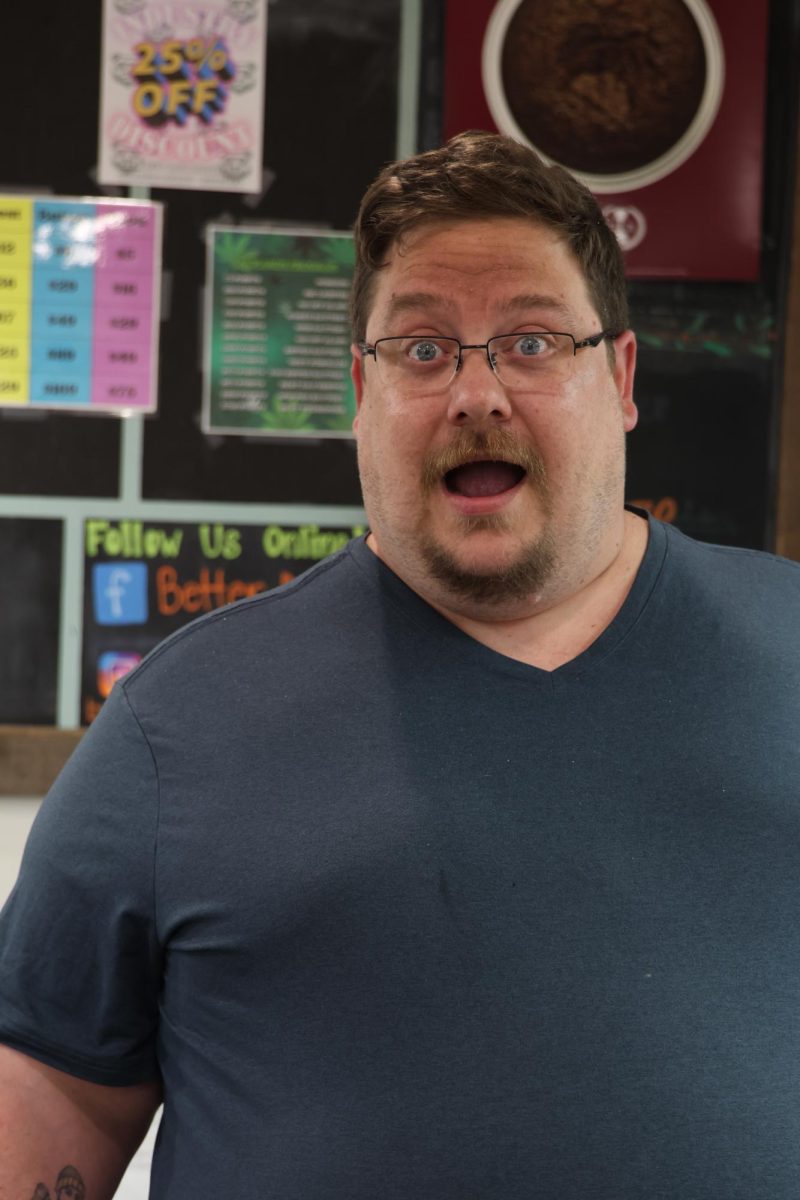

When Jeremiah Civil, a Marine Corps combat veteran who served from 2001-2005, went in for his recent medical evaluation at the Department of Veteran Affairs in Portland, he was asked a series of basic questions about his health and habits. “Do you smoke marijuana?”

“Yes,” said Civil.

“Look, I understand. In fact, if it were up to me, I might even say it might be okay,” replied the VA officer. “It might even be a good thing. But let me read you this pamphlet.”

The officer proceeds to quickly read through a short lecture prepared by the VA about how marijuana is illegal under federal law and they do not support its consumption.

Civil has Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and says that cannabis helps him cope with his everyday symptoms. He was not always a habitual smoker. The intense anti-cannabis culture of the military had convinced him it was not an option for years after his service. Eventually, with some guidance, he gave it a try.

“It changed my whole life,” said Civil.

He takes a deep hit from his rubber green bong. He sits in the living room of his government-owned house on site of the Federal Fish Hatchery he also works at, near Estacada, Oregon. There is a cascading display of flags hanging from his ceiling in the living room. In the center is the American flag. On one side is the Department of Interior and the Oregon state flag. On the other side is a banner for Prisoner of War and Missing in Action. “That was kind of our flag,” says Civil, referring to his role in Mortuary Affairs in the Marines. And behind the banner is the red flag of the Marine Corps. “I have my home, my country, who I work for now, and the two cults I belong to,” he jokes. His white pit bull rescue, Gunner, rests lazily on the couch next to him.

“It creates distance between the present and the past within your memories,” said Civil, referring to what cannabis does for him.

He explains his concept of the separation between a person’s resting baseline and anxiety. There is a gap between the body’s resting state for muscle tension, heart rate, adrenalin levels and the threshold of fight-or-flight. Increasing stress closes that gap. But when trauma happens, the body decides it can no longer survive at that low resting baseline. After trauma, the body resets itself to a higher baseline closer to that fight-or-flight threshold, shortening the distance between resting and alarm. This, he explains, is why people with PTSD are more spooked by sudden noises, bright flashes of light, large crowds and so on. These triggers can become an everyday occurrence with trauma such as PTSD.

But for Civil, cannabis slows that progression towards fight-or-flight. He explains that smoking gives him enough space to recognize when he’s about to have a panic attack. He gets more time and can identify it and sometimes even stop it before it overtakes him. “It gives me a little bit more, before it kicks in,” he says. “Enough time to think and become aware.”

It took several years after he left the Marines for Civil to settle on the idea of using cannabis as a tool. When he began experiencing symptoms from his trauma, he went to the VA, where they prescribed antidepressants such as Wellbutrin and Effexor. While the depression was being treated, his anxiety was left untamed. “It was just amplified,” he said. He describes not sleeping very well and always being on edge. He was married at the time. After a particular incident where he got angry and broke everything in the house, his wife sent him to the VA where he received in-patient treatment.

They switched his Wellbutrin to Paxil and added Xanax and Klonopin for the anxiety. However, the addictive properties of the Benzodiazepines overtook him. His compulsive nature would lead him to taking Xanax to the point of full emotional disconnection.

“You could come in here and kill my whole family, and I’d be like, ‘eh shit. Whatever. I don’t care,’” he remembered, taking another rip from his well-packed bong. His dog, Gunner, makes a lazy canine groan on the couch next to him.

The new drugs changed things for him, but not for the better. In 2009 Civil sought counseling at the VA, but quickly terminated that when he had an explosive outburst of frustration when the staff counselor couldn’t relate to having ever experienced combat.

That’s when he was referred to the Portland Vet Center, a community-based counseling center that specializes in PTSD and military sexual trauma. It’s a branch of the VA established in 1979 by congress, initially to assist with societal reintegration of veterans from the Vietnam War. This is where Civil finally found the guidance he needed.

His next counselor was a combat vet this time. Civil described him as a “hippy type” with gauged ears. The counselor immediately advised Civil to get off the Benzos. He suggested quitting alcohol, coffee and energy drinks, and to start smoking a lot of weed, to help with weaning off his anti anxiety meds gracefully. He helped Civil get his medical marijuana card.

Within a few months he had successfully kicked the Benzos, his mood had stabilized and he was finally starting to get a few decent nights of sleep. “It was all about finding the right counselor,” said Civil.

His favorite strain quickly became Sweet Tangerine. “It gives me energy without anxiety,” he said. Another one of his veteran friends used grow it for him but claims he can’t find it anywhere. Now he says he just goes for what’s cheap.

Finding the right counselor was a turning point for Civil. Among cannabis use, he adopted a collection of activities to help manage his mental health. Until recently, he was a Warrior leader at group therapy sessions for the Wounded Warrior Project. “People tend to open up more in those situations than they do in a counseling session,” said Civil. “Sometimes you can have some beers and buds; loosen things up.” He jokes about starting a marijuana therapy group complete with a talking-bong to pass around. He continues with counseling, and occasionally volunteers with veteran nonprofits.

He takes the opportunity to rip from his rubber green bong again. Smoke drifts amongst his assortment of flags in the high vaulted living room ceiling.

Jeremiah Civil discusses marijuana as a post-traumatic stress disorder treatment Friday, March 22, 2019, at his home near Estacada.

Using cannabis to cope with trauma is not a cure-all. There are many reasons why someone may not be able to or want to use cannabis, and it’s not a cure for every internal struggle combat veterans suffer with. Civil’s story is simply a case in which cannabis was a missing piece among many that ultimately helped him get his life back.

“Getting off the meds and getting into weed opened me up to trying other things,” he says, referring to treatments for his mental health. In 2011, he attended a Native American sweat lodge ceremony, which he credits to eliminating his nightmares.

Since he got rid of his nightmares, Civil no longer feels like he needs cannabis for sleep. He says he used to rely on it for bedtime. But every now and then, his anxiety catches up with him in the night, finding himself waking in the middle of a panic attack.

Civil used to sleep with a loaded gun. Heart pounding out of his chest, and muscles tense, he reaches for his night stand, looking for the tool he’s learned to trust most as a veteran of war. He puts it up to his face. He flicks a lighter. He’s replaced the loaded gun with a loaded bong. He takes a long deep breath, and as he exhales, his muscles relax, his heart beat goes down, and his mind settles.