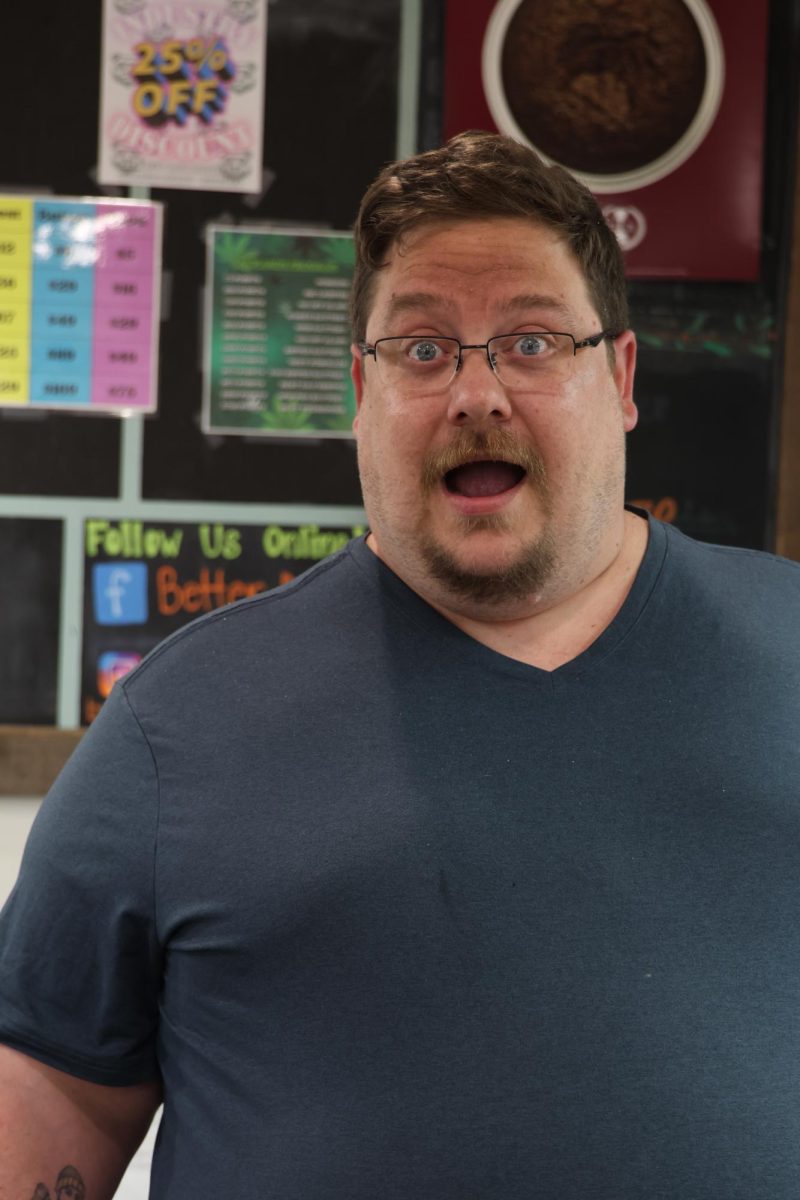

As legalization sweeps the nation it becomes easier and easier to take the medicinal qualities of cannabis for granted. And yet, this progress is only possible because people with disabilities have fought tirelessly for the right to relief from mental and physical pain. I sat down with Sai Marie, a local cannabis user who lives with fibromyalgia, partial hearing loss, anxiety and depression, to learn more. We discussed medicinal cannabis, coming to terms with mental illness and Sai’s experience growing up as a biracial native woman.

At 35, Sai Marie is an accomplished author of poetry, sci-fi and fantasy short stories as well as a mother of three. She radiates the confidence unique to published poets and sports a large turquoise necklace, a gift from her uncle. “From the Res,” she says.

In the golden light of Café Roma, between sips of raspberry mocha, Sai tells me of a more challenging time in her life. She dropped out of high school so she could put more energy into motherhood, and then she went through a difficult divorce in her early twenties. Through all of it, Sai was suffering from depression as well as a mysterious, generalized pain she would later discover to be fibromyalgia. But when she sought relief from doctors, the pills they gave her robbed her of her passion for writing. “I’m a creative person,” says Sai. “I’ve taken Celexa, things like that. They made me feel zombified. That’s no way to operate. It’s existing, not really living.”

Managing the balance between wanted and unwanted effects is a challenge when taking any medicinal drugs. And yet, side effects that change our sense of who we are, especially on an ongoing basis, are especially hard to accept. As Sai tells me, “The thing about my disabilities is that they’re constantly treatable; they’re not curable.” Unwilling to give up her art, and to a greater extent, her sense of identity, Sai Marie quit her prescriptions and started searching for an alternative.

At 24, Sai Marie started using cannabis medicinally, but not without some initial hesitation. “There was a point in my life when I was totally against it,” she says. “You know, I was a nineties kid and D.A.R.E. was a big thing back then.” Although Sai had tried cannabis in her younger years, it took a close friend who was fighting cancer to convince her that it could be used as medicine.

According to Sai, the choice to self-treat her fibromyalgia and depression with cannabis was less a matter of peer pressure and more of an empirical deduction. “I experienced the benefits myself so I can’t say that it doesn’t work. I’ve changed my life completely since then.” Much of this change has been Sai’s acceptance of mental illness and trauma as a permanent part of her, but not a defining part. “Cannabis allowed me to step outside of that emotional grey area, that gloomy cloud, and look at life and go, okay, this did happen, but it’s all about my perspective and what I want to do with my time.” For the kind of chronic conditions that Sai lives with, ultimate cures are not a possibility, but relief and perspective are. One factor in her choice take treatment into her own hands was growing up with a mother who defied disability stereotypes and encouraged her to explore native herbal medicine.

Sai inherited genetic hearing loss from her mother, but she also inherited the confidence to live with it proudly. As we talk she combs her hair behind her ear to reveal a hearing aid, pale and smooth as a shell. She still has about ten percent of her hearing, she tells me. Her mother had it much harder: a Cherokee girl growing up in the sixties in a silent world. “They wanted to send her to a special school. They put it in her head for a long time that that’s all she could do. Now she’s a psychologist, she’s a very successful woman. I had that as a mother to look up to.” Sai goes on to tell me how her mother made her conscious of her Cherokee heritage. “Since I was a little girl, it was very present in my life that I was biracial.” Part of this presence came in the form of native herbal medicine, a tradition that Sai’s mother taught her long before she conceived that cannabis might have a place in it. Turning towards the future, Sai wants to continue the practice of herbal self-treatment for her own children. But sometimes laws intervene.

For Sai Marie’s adult children, the revolution in how we think about self treatment for pain can’t come soon enough. “My two boys are terminally ill,” Sai tells me. Both of them suffer from muscular dystrophy, a condition that slowly breaks down the skeletal muscles. CBD can help alleviate the chronic aching associated with this condition. “But they live in Tennessee, so they can’t get some of the benefits that they need. They kind of think it’s sad that they can’t have it.” Historically, Sai’s boys’ experience has been the rule rather than the exception. It’s only very recently, mainly thanks to people like Sai Marie raising their voices, that the ability to seek relief from chronic pain has been viewed as a right. And yet, now that the right to relief has taken root in the national consciousness, the swift pace of its adoption into mainstream culture gives Sai hope for a broader acceptance of disability and mental illness going forward. As Sai tells me, “If it starts as simply as giving someone a plant that can help them, then what can we do to change our world?”