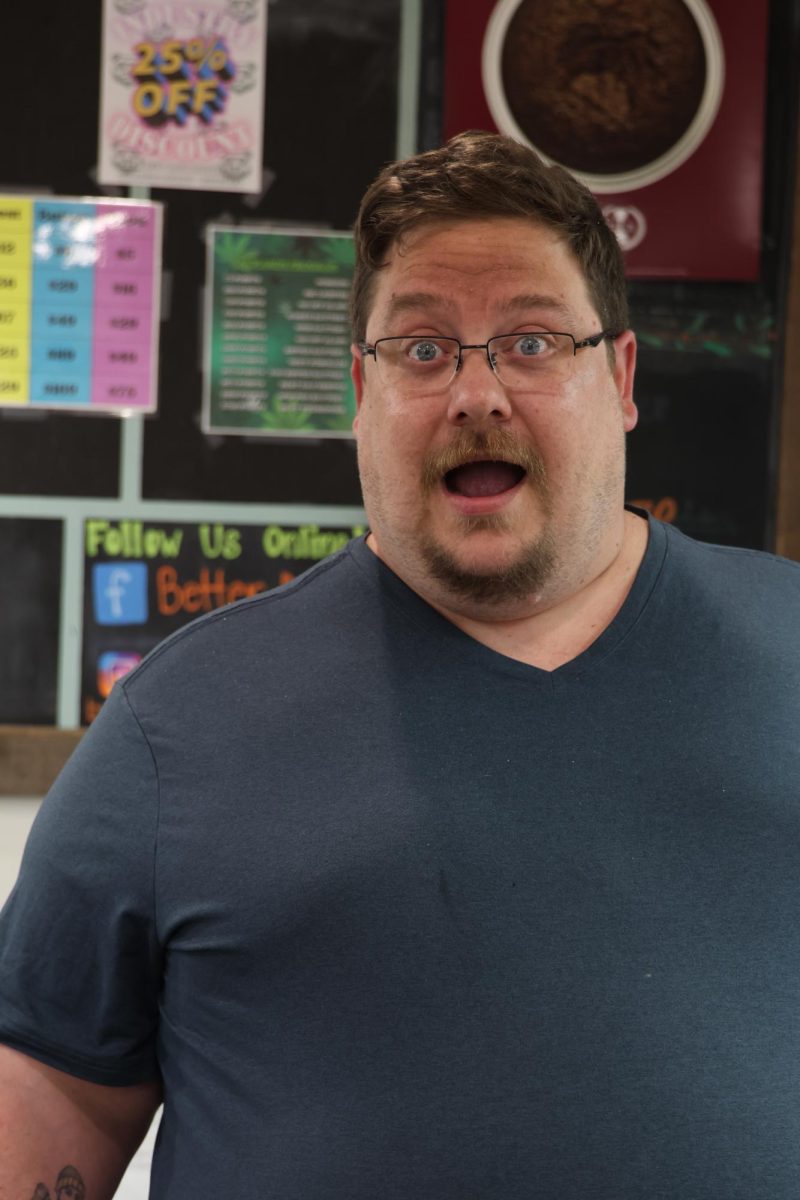

“I never had any intention of writing about cannabis,” Dr. Kaitlin Reed, assistant professor of Native American Studies at Cal Poly Humboldt, said. “I can’t wait to not be the weed person.”

For Reed, it’s as if there was no choice in writing about cannabis. As a Yurok and Hupa tribal member witnessing environmental violations in ancestral territories and throughout U.S. history, Reed saw the urgency and concern over landscape devastation paired with the current lack of critical analysis. Modern cannabis cultivation and the market it drives are built on the same foundation of exploitation of Indigenous people by white colonizers as seen with other natural resource industries such as gold, timber and fish.

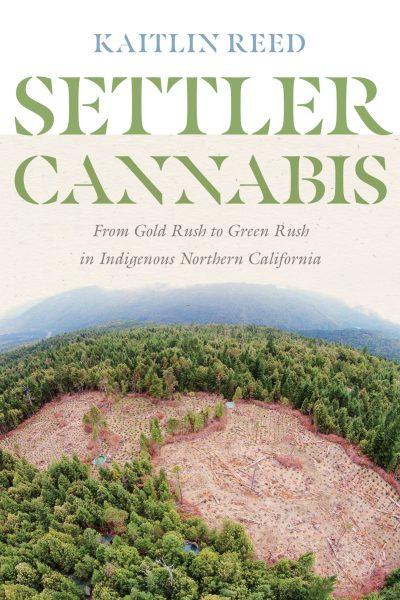

Reed’s upcoming novel, “Settler Cannabis: From Gold Rush to Green Rush in Indigenous Northern California,” is one of the first to contextualize cannabis’ industrialized production as violence against Indigenous lands, bodies and water, particularly in California and Yurok homeland. Rather than a simple exposé of the industry, the novel critiques the ongoing resource rushing since the time of invasion. Although many tribes have different relationships with cannabis cultivation, Reed’s narrowing to Yurok reflects the broader Indigenous environmental justice issue as part of the historical pattern.

To understand the problem, we need to understand the people impacted. The Yurok tribe is located in northwestern California spanning from the mouth of the Klamath River and 40 miles up. According to Reed, the concentration of cannabis grown in northern California is an outcome of prohibition and not the ecosystem’s ability to sustain large quantities of cultivars. There’s a lack of ecological decision-making in this landscape of biologically sensitive watersheds that’s “fundamentally unsustainable.”

As a response, the Yurok Tribe reached out to California Gov. Jerry Brown for assistance and formed Operation Yurok as a collaborative initiative between tribal, federal and state law enforcement, including California National Guard Counterdrug Unit, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Fish and Wildlife, Water Quality Control Board and others.

During the five years of operation since its inception in 2013, Operation Yurok eradicated approximately 70,000 cannabis plants from 43 sites growing illegally by non-tribal members on tribal land. These wayward weeds were “responsible for robbing millions of gallons of cold water from several tributaries that feed the Klamath River,” leaving 300-plus families on the east side of the reservation without basic needs met, according to the tribe’s press release.

“Operation Yurok tribally spearheaded cannabis eradication because trespass cultivation was literally sucking entire streams and tributaries dry,” Reed said.

Trespass grow sites revealed evidence of environmentally devastating land misuse. During Reed’s internship with the then-called Yurok Tribe Environmental Program, she witnessed catastrophic impacts on her tribe’s land: The Klamath River was suffering from excessive dangerous chemical fertilizers and trash dumping that contributed to the decline of fish populations such as salmon, a sacred specie and key food source for the tribe. The Yurok Fisheries Program found adult Chinook salmon to be infected with Ichthyophthirius multifiliis (Ich) – the same disease prevalent in the 2002 largest fish kill of American history.

The 1970s salmon wars was fundamental to Reed’s thinking about the series of violence on Indigenous lands, bodies and water throughout American history that led to her novel’s thesis. The Department of the Interior issued a moratorium on fishing because “settler fishing industries had essentially decimated salmon populations,” Reed said. Tribal fishermen “were brutally attacked and imprisoned by Fish and Wildlife law enforcement.” This moment of militarized presence isn’t a one-off; this horrific case study depicts the systemic genocide and ecocide that is just as prevalent in all extractive industries, like gold and timber rushing, as it is now seen in the green rush.

Reed described grow sites being spaced out to avoid being caught by federal law enforcement. Rather than having one large site, growers dispersed them into smaller blocks linked by trails. When wildlife follows these trails, they wander into cultivation sites where they are shot or poached.

“We also see a lot of intentional poisoning of wildlife to remove crop interference,” Reed said. “Rodenticides, also known as rat poisons, don’t actually kill the animal: It stops the production of vitamin K so their blood can’t clot. They essentially bleed internally, slowly, causing bioaccumulation through the food chain.

One of the big issues for trespass cultivation is that these sites were never intended for long-term use, so they weren’t building latrines and outhouses, Reed described.

“There was one site with over one hundred gallon buckets filled with human feces. The levels of E. coli in our water system were insane. Why does it fall to the Tribe to literally clean up settler shit? What makes the state of California think it’s equipped for the Green Rush when they still haven’t cleaned up after themselves from the Gold Rush?” Reed said.

“Why does it fall to the Tribe to literally clean up settler shit?

– Dr. kaitlin reed

What makes the state of California think it’s equipped for the Green Rush when they still haven’t cleaned up after themselves from the Gold Rush?”

In Reed’s alternative envisioning, the deindustrialized world of cannabis lacks an industry altogether because “there really isn’t a need for an industry.” She correlates cannabis with any other individually consumed crop, such as vegetables, that aren’t codified and surveilled. With federal and state-regulated approaches, overproduction is inescapable in capitalism. But before we can decontextualize cannabis from colonialism, we must first return land.

“The goal is to lure in unsuspecting cannabis enthusiasts and force them to learn about settler colonialism and histories of genocide and resource extraction in California, and why that’s not part of ancient history, but still very much shapes the present,” Reed said. “It isn’t designed to be an exposé of the cannabis industry. Many of the critiques I’m leveraging against cannabis cultivation are also applicable to commercial fishing, fire suppression policies, mineral extraction, fracking and pipelines. The list goes on: Cannabis just happens to be the thing that is in my ancestral territory and threatening my rivers right now at this moment.”

Situating cannabis in a broader environmental context is vital in the era of another California resource rush. With wealth accumulation disproportionately benefitting some while at the cost of others, the novel traces patterns of historical exploitation to propose an alternative reality that drifts away from the commodification of nature. Releasing in May 2023 by the University of Washington Press, the book is crafted to be accessible to a broad and diverse readership so anyone from community members to students in Native American studies to sociology can interpret it without the need for an academic jargon translator.

“For me,” Reed said, “this book is Indian country’s foray into contemporary cannabis discourse.”