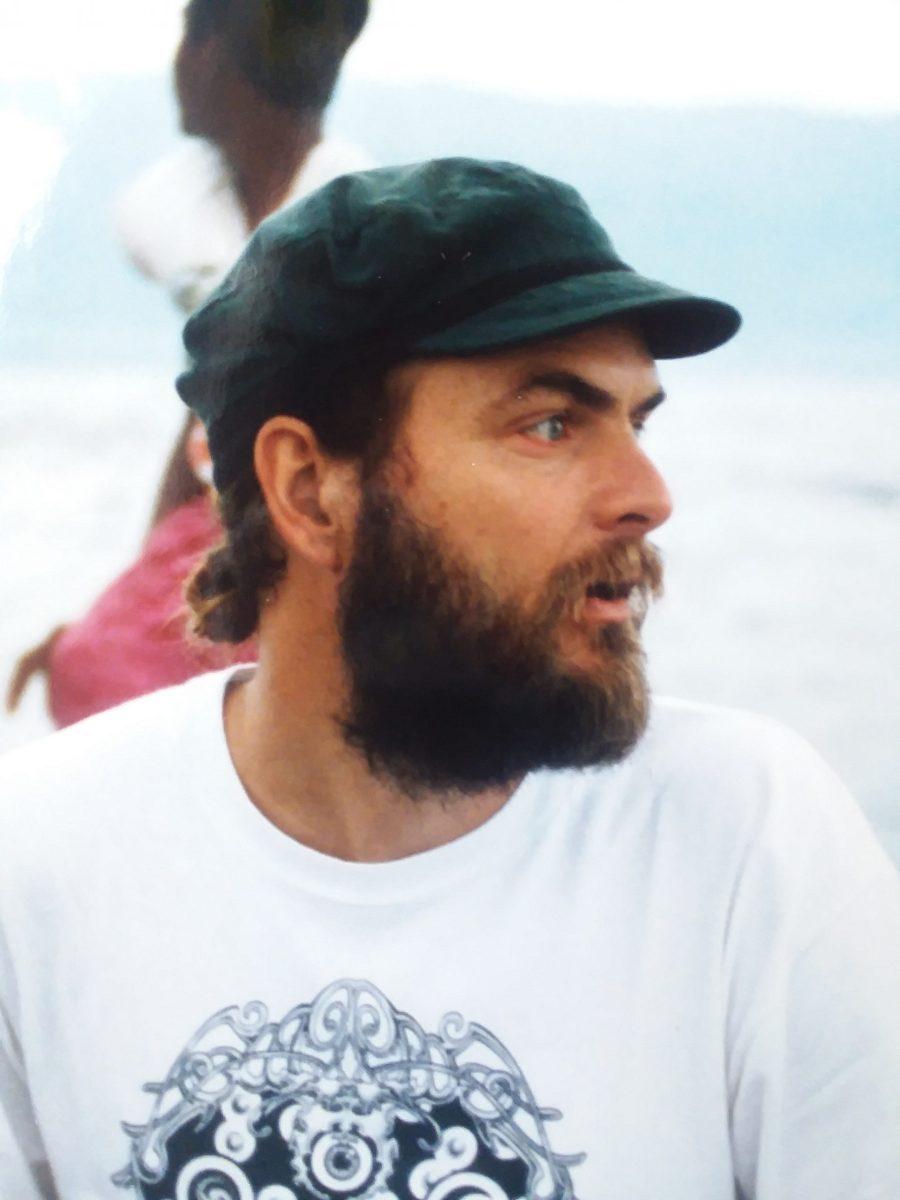

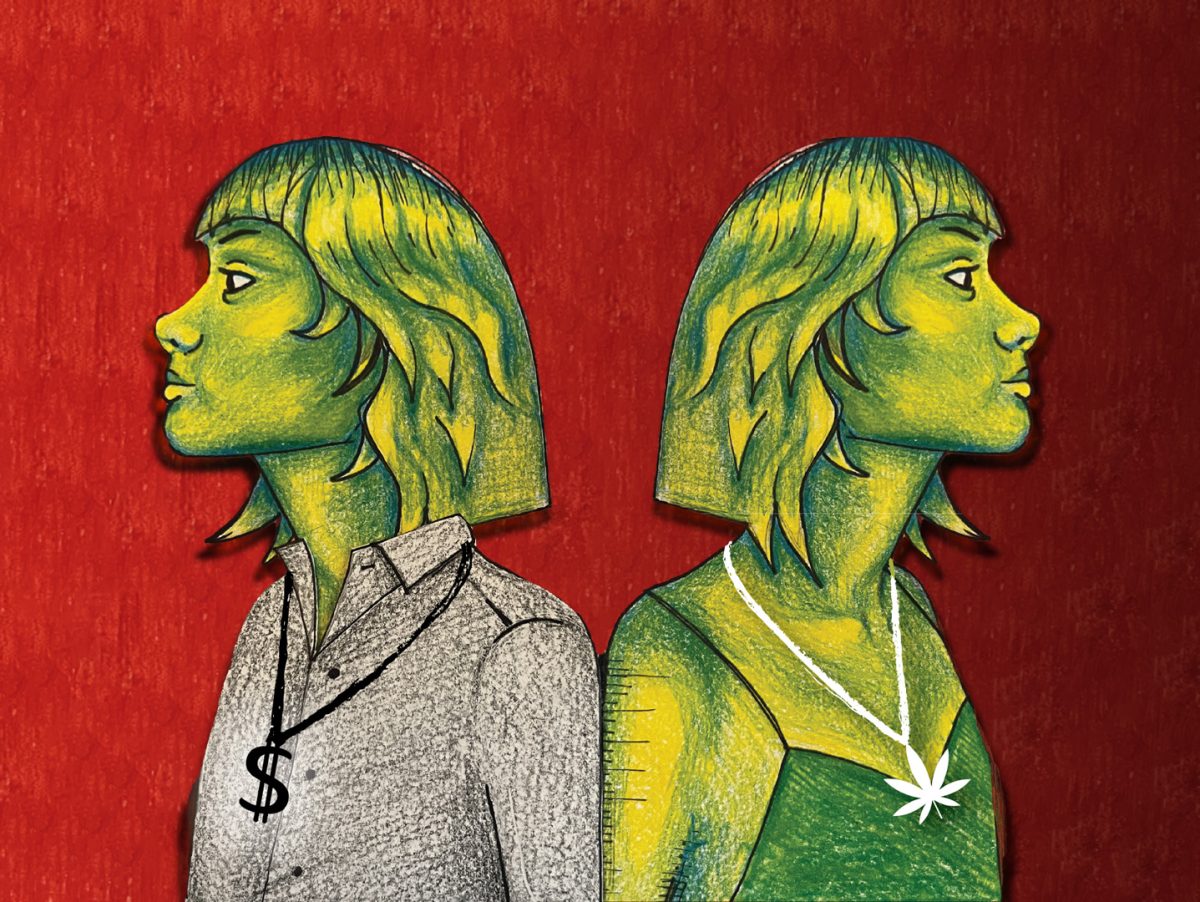

Six years after legalization in Oregon, social perceptions of cannabis users are starting to evolve. From toking podcasters to weed-infused weddings, cannabis is shedding the reputation of Reefer Madness and assuming a more nonchalant attire in the public eye. Yet the scars of old prohibitions run deep, and while popular culture moves on, the devastation of the war on drugs is still felt by many Oregonians who were caught in the crossfire. I sat down with James Lyons, a retired craftsman, Reggae enthusiast and cannabis convict to discuss the lasting damages of criminalization and the potential for social healing. In our interview, Lyons revealed the violation and absurdity which underscored his family’s years-long struggle with the criminal justice system. Perhaps most importantly, Lyons described how the injustice with which he and his loved ones were treated tainted his perception of the government as a whole.

In 1985, James Lyons was in his mid twenties and living as he pleased. After a spinal injury had ended his career as a house painter, Lyons became an artisan craftsman, gardener, and connoisseur of Reggae. He spent half his time touring with his favorite bands, helping them out at shows, selling his creations on the side and discovering a deep affinity for Rastafarian culture and religion. The other half of his time was devoted to his home in the backwoods of Washington County where he lived with his partner and teenage niece. It was there that Lyons constructed a small greenhouse to grow “herb,” mainly for personal and social use, in accordance with the spiritual traditions of Rastafarianism. Lyons assumed that the remoteness of his domicile would protect him from the law. According to Lyons, he was so relaxed, so filled with the flow of every living thing, that when a cannabis plant self-seeded in his front garden he couldn’t bring himself to pull it up. “I let it grow,” he tells me. “Live and let live, you know. I thought, this is meant to be.”

Unfortunately for Lyons, he had spared the Judas of cannabis plants. The police had been surveilling his property by airplane for months, but the mere presence of the greenhouse out back was not sufficient evidence for a warrant. But when the little-herb-that-could grew and became visible from the driveway, it gave the authorities all the justification they needed to bust down the door and bring Lyons’s life crashing down around him.

Lyons returned home one day to find his house torn apart and an official note setting a court date for him, his partner and his niece. “It was my thing and yet they lived with me and so they charged them too,” says Lyons. “My niece just happened to be in the house at the time. She’s always had trouble. We raised her for a while because she had been passed around in foster care, you know, so we took her in for maybe four or five years until she was old enough to go out on her own. She really didn’t need this to happen when it did.” Compounding this invasion was the fact that James’ partner knew the invaders. In fact, due to her job at city hall, they were her colleagues. “They knew all about what was going to take place for a month in advance,” Lyons tells me. “She’s working around these police officers and then all of a sudden they’re in our house and one of the first places they went was to our bedroom and tore our drawers apart. The whole place was trashed. That feels kinda violating, you know?” As he put his home back together and waited for his court date, all Lyons could hope was that judge would be reasonable. Unfortunately, it would seem 1985 was a bad year for reasonability in criminal justice when it came to cannabis convictions.

When the court date finally came, Lyons and his lawyer marshaled his argument along two main lines. The first was that his partner and niece were incidental to the whole affair, and therefore should not even be charged. The second was that his cannabis grow was an expression of the religion of Rastafarianism rather than a commercial venture, and should therefore be treated more lightly under the law. This was a stouter defense than it might at first sound. Lyons had personal and legal precedent to back it up. “I’d been to Jamaica three times prior to that and had studied Rasta there. It really became part of my life.” Lyons had also studied under spiritual leaders of the Havasupai Nation in the Grand Canyon and knew there was legal precedence for the use of certain drugs in native ritual practice. Lyons thought he had hired the perfect lawyer to present this defense, given that the man produced ticket stubs to a Bob Marley concert at their first meeting. This opinion quickly changed when he saw how his lawyer, the prosecutor, and the Judge interacted.

“The main thing that I got out of the court proceedings” Lyons confides, “ is that the whole legal system is all intertwined together whether the lawyer is on your side or not. He’s friends with the prosecuting attorney and they know the judge and after work they go play golf together,” said Lyons. The bizarreness of the trial was compounded by the Judge who presided over Lyons case. “He said if I was his son he would take me in the basement and beat the shit out of me,” says Lyons. “I thought, you know, that’s kinda odd.” Despite this behavior, Lyons Judge ultimately passed the relatively lenient sentence of three year’s probation for Lyons and his partner. They were overjoyed, but they celebrated too soon. According to Lyons, when the pair subjected to a polygraph test as part of their conviction, they admitted to having used cannabis after their arrest but before their conviction. At the time the test administrator said this was not a problem. “A month later when we went back in to see our probation officers we were both arrested and thrown in jail with a six month sentence. I don’t know how that works but that’s how it did,” said Lyons. This was confirmed by Washington county public records which show that his initial three years probation was revised to a six month sentence upon violation of his probation. As arbitrary as this bait and switch seems to Lyons, he feels the true absurdity of the criminal justice system presented itself in his niece’s juvenile trial.

Justice is supposed to be blind, but not deaf to common sense arguments. Yet such was the case in the trial of Lyons’s niece. Lyons was planning to make the same case he made for his partner, strengthened by an appeal to his niece’s young age and fragile emotional condition, in the hope of getting her off entirely. “My niece was afraid to represent herself or to say anything so I said, ‘I’m not,’ I’ll gladly go and say what I have to say.” But things started to go south before the trial even began. “Five minutes before I was to go to court and represent my niece the prosecuting attorney switched judges.” Lyon’s previous Judge, with whom he had built something of a rapport, was replaced by a new Judge who, according to Lyons, allowed the prosecution’s attack on his character to overcome Lyons’ defense of his niece’s wellbeing.

“So this new Judge says, ‘Right there the prosecution’s proven you’re a liar. I’m not gonna hear another word out of you or I’m gonna put you in jail.’ I wasn’t aggressive or anything, I was just trying to understand what happened. It made me realize the legal system is corrupt.” Lyons’ niece paid a heavy price for the new Judges sternness. “She was put on probation and that wasn’t something she could deal with at the time. It went on for almost ten years for her. That probation just kept going on and on, and at one point they put her in a womans’ prison in Portland for at least nine months.” Lyons’ niece had nothing to do with his cannabis grow, but she suffered from addictions of her own. According to Lyons, rather than treating her as a victim of these addictions, rather than helping her find a way free of her troubled past, the legal system penalized his niece and kept her locked in a cycle of endless probation. After wrestling with the legal system for over a year, in the case of Lyons and his partner, and over ten years in the case of his niece, none of them wanted anything to do with criminal justice.

Lyons doesn’t smoke herb anymore and his niece has escaped from the cycle of incarceration. “Life changes, you have kids and go through divorces and get different perspectives. Still, I stand with how I felt back then. I understand who I was then. Herb opened up a lot of doors in my life and taught me a lot of things, even though I don’t use it now,” says Lyons. He says he doesn’t regret growing cannabis because of the friendships and spiritual awakenings it offered him. What he regrets are the policies which made that pursuit a crime. “I think it’s been proven that the war on drugs hasn’t really worked,” he tells me. At this point in our history, that seems certain, and fortunately, state law-makers are starting to agree. Still, as we revel in our newfound liberties, it is not enough to simply end criminalization of cannabis. To heal as a society, we need to actively reincorporate former “criminals.” That means pushing for the expungement of non-violent drug offenses and reevaluating addiction as a public health issue rather than a criminal one. Casual drug use is the least of our worries in a world so full of injustice, while the underlying causes of serious drug abuse are worsened, not alleviated, by persecution and punishment. As we’re tugged by the authoritarian undercurrents of an earlier time, the complexity of the modern world can leave our political ship somewhat rudderless. Yet there is wind in the sails of cannabis decriminalization, mostly due to the prevalence of stories like this one. As Lyons tells me: “We gotta try and change the laws.That’s how our system works. If enough people just keep pushing in that direction, eventually it’ll change.” This is no longer a matter of personal interest for Lyons. After all, he stopped smoking years ago. Now it’s a matter of principle.