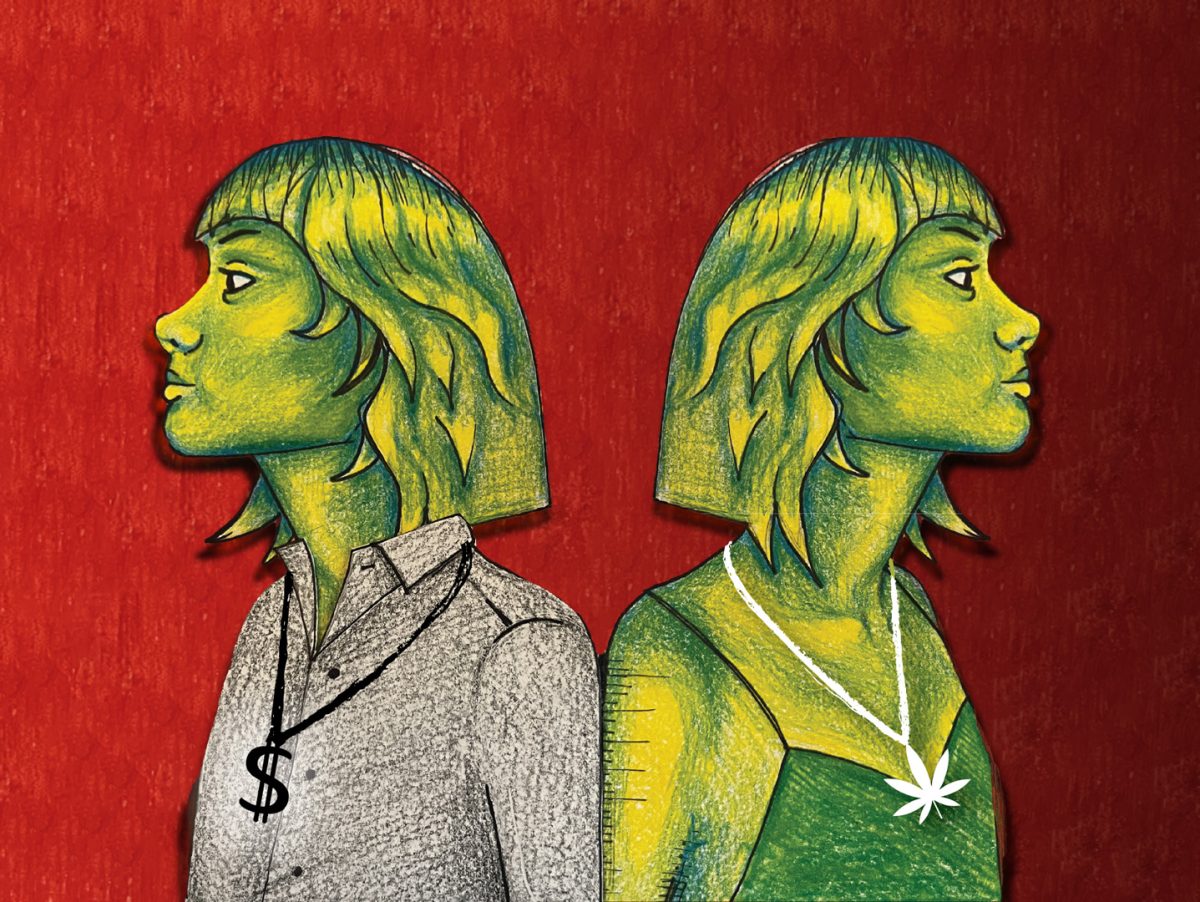

Since cannabis was legalized in Oregon six years ago, on Oct. 1, 2015, it seems like a thing of the past to remember how nerve-wracking being a cannabis connoisseur once was. Public opinion about cannabis has changed greatly over the last few years. It almost seems like smoking a joint is less offensive than smoking a cigarette. But things used to be harsher than we even realize back when society truly demonized cannabis. It was not only the smokers that had to worry about criminal charges, but also the journalists that covered such a turbulent topic.

The Daily Emerald wasn’t always independent from the university, and campus officials and the authorities hounded one such journalist named Annette Buchanan. After being named managing editor of the Oregon Daily Emerald in May of 1966, Annette wrote an article titled, “Students Condone Marijuana Use.” The ensuing legal battle and repercussions would not be forgotten by the State of Oregon, the University of Oregon or the future of journalism itself.

In the article,tudents under pseudo names vented their frustrations surrounding the views and misconceptions that the general public held about marijuana at the time.

“Pot is not like alcohol,” explained Bill, one of the seven students Annette interviewed. “You have complete control. You don’t lose yourself.”

“Who does the middle class or the government think it is that they can tell people what to do?” asked Joe.

The students expressed their distaste about myths similar to those we’ve also heard in more recent years. They complained about how society blamed marijuana for leading to harder drugs, like heroin. However, the students knew that it wasn’t the plant itself that caused its association with hard drugs and crime. It was the fact that it was illegal and therefore only dealt with by the black market. If something isn’t regulated or following a set of standards, it’s bound to be surrounded by shady components.

The students had excellent points about how using marijuana helped “enrich their (intellectual) experience.” They argued that it could even benefit an alcoholic or otherwise heavy drinker to cut down on their drinking and possibly help them switch to simply smoking pot occasionally. They even recognized that being sentenced to jail time for using or possessing cannabis was not a deterrent but a way for society to destroy a college student’s career before it even began. The students could not have known how significant their anonymous accounts would come to be.

It is essential to explain why such an article was published by Buchanan, who herself did not consume cannabis. On Sunday, May 22, students in the lobby of the Student Union voiced questions regarding why the Emerald featured so many seemingly anti-marijuana stories. Buchanan assured them that the Emerald was not purposely trying to condemn them or send such a message. She promised to find out what she could do to alleviate their concerns. The news should be able to present the views and opinions of every one of its readers, after all.

While proofreading an editorial page endorsing Charles O. Porter over residing Lane County District Attorney William Frye, Emerald Editor Phil Semas suggested Buchanan interview UO students about marijuana. On election day, May 24, “Students Condone Marijuana Use” was published in the Emerald.

Too strange a coincidence was it that a week later, on June 1, District Attorney Frye issued subpoenas for Buchanan, Semas, former Emerald Editor Chuck Begs and former Managing Editor Bob Carl. Two days later, all four appeared at the Lane County Courthouse with Attorney Arthur Johnson. The Grand Jury observed as Buchanan was grilled by Frye first, who immediately demanded the names of the seven students featured in her article. Buchanan refused.

Buchanan explained her decision to the Grand Jury citing five reasons: First, as a journalist, Buchanan could not, and would not, breach the code of ethics of her major and profession. Second, to do so would be violating the constitutions of both Federal and State levels, which guaranteed freedom of the press. Third, as a State of Oregon employee, the knowledge was privileged communication. Fourth, the demand was outside the appropriate scope of the Grand Jury. And finally, Buchanan was not afforded legal counsel during the hearing. Frye was more than unhappy and tried to twist the information out of Buchanan by comparing withholding the identities of the cannabis-smoking students in her article to that of rapists and murderers.

Twice before the Grand Jury, Buchanan protected the seven students’ identities, which resulted in her being held in contempt of court and fined $300. This was mainly because Oregon did not yet have a shield law, a statute that protects journalists’ right to refuse to disclose or identify their sources. Publisher of the Oakland Tribune and former Republican Senator William Knowland offered to pay Buchanan’s fine. Frye was the first District Attorney of Lane County to make a name for themself by prosecuting drunk drivers. It makes sense Frye would go after cannabis, especially when the article was on the front page.

On Dec. 4, 1967, Attorney Johnson filed an appeal through the Supreme Court of Oregon. Unfortunately, the verdict of being held in contempt of court was upheld. “The courts have held the rights of privacy, freedom of association, and ethical convictions are subordinate to the duty of every citizen to testify in court,” states the official State vs. Buchanan court document. Nevertheless, by April 1973, the Oregon House passed Senate Bill 206, ensuring Oregon journalists’ right to protect the identity of their confidential sources.

Next time we light one up, let’s remember Annette Buchanan, a courageous and honorable journalist. While she was only taking the advice of Emerald Editor Semas by trying to give students their own voice to discuss marijuana use, Buchanan made a name for herself by following through with the promises she made as a journalist and protecting those sources. At the young age of 20, even in the face of so many threats, from the courts and anti-cannabis individuals, she firmly held her ground. She inadvertently helped Oregon enact its shield law, preventing other journalists from going through similar nerve-wracking experiences. She was a copy editor for the Oregonian for years 1975 to 1997 and even operated a farm with her husband, Michael Conard, near Sandy, Oregon. Buchanan lived to be 67-years-old, leaving behind a shining legacy for all journalists to aspire to.

“She felt bound by her conscience, her pledge and her word.” – Attorney Arthur Johnson, The Oregonian, June 29 1996.